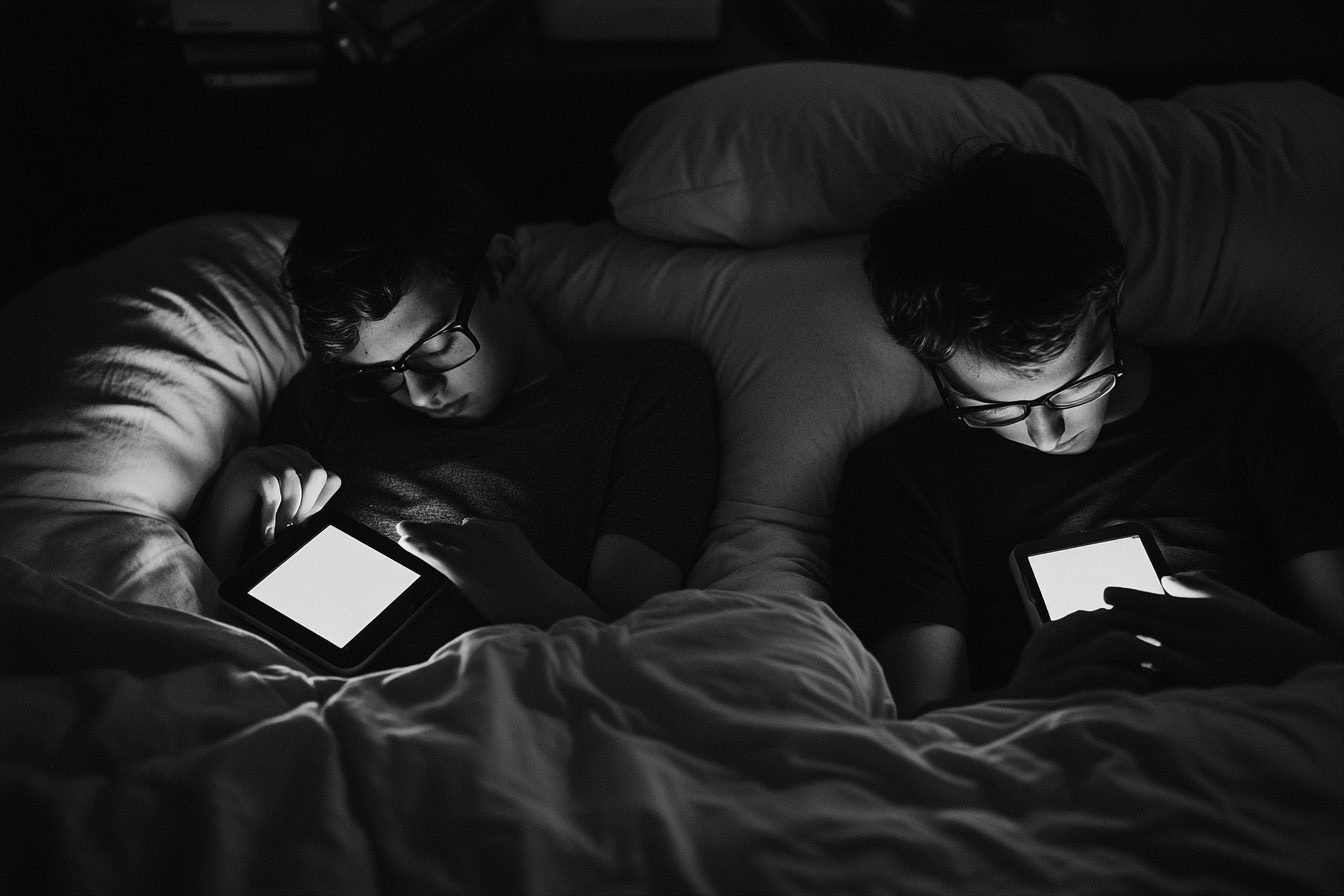

It’s 1:17 AM as I type these words. This is my third consecutive night working in a row, and I have a 7:30 meeting tomorrow morning. My body aches with fatigue, and my digital device has turned into the proverbial ball and chain. Yet here I am, scrolling, tapping, and consuming digital content with the focused dedication of someone who doesn’t have responsibilities in six hours.

This isn’t insomnia. The Chinese call it “bàofùxìng áoyè” – revenge bedtime procrastination. It’s the decision to sacrifice sleep for leisure time, a small rebellion against a work-dominated day.

I didn’t know this behavior had a name until recently, and there’s something darkly comforting about that. Psychologists have labeled and studied this phenomenon, marking it as a form of self-sabotage. Instead of assuming I was just tired and making a bad decision, I realized I can now claim to partake in a globalized self-destructive notion. How validating…

No matter how much I wish it to be different, the routine remains unchanged. Work ends. Dinner with the family. The dishes are rinsed and put away. The kids are bathed, read to, and tucked into bed. The chores are done. The to-do tasks are checked off. And at 10 p.m., I get the first taste of personal freedom. The choice that tickles the logic would be sleep, which, after a busy day, is the one thing my body needs. But I opt for the digital version of empty calories: social media feeds, YouTube deep dives, and articles from my “to read” folder, which should honestly be labeled “read when you should be sleeping.”

What makes this behavior weirdly self-destructive is that I’m fully aware of the consequences. I know the research on sleep deprivation. I understand the long-term impacts of chronic sleep debt. I have lived through the cognitive fog, the annoyance, and diminished the productivity that comes the next day after these late-night screen sessions. Yet, for some reason, I want to keep repeating the same choice over and over, as if I’m a clinical trial participant with no control group in sight.

The irony lies in the fact that I spend my waking hours crafting pieces on the topic of digital wellness and the responsible use of technology. I advise people to self-regulate their screen time, set tech-free zones and tech-free periods. “Never bring your phone to bed,” I argue with the misplaced authority of someone who hasn’t been ensnared in a TikTok vortex at 2 AM on a Tuesday. My hypocrisy is profound, deep and late into the night.

So what’s this self-inflicted pain we put ourselves through? What convinces us to engage in this bizarre brand of self-sabotage that somehow feels, in a contradictory way, like self-care?

In my case, it began during my corporate tech years. My waking hours were so rigorously swallowed by meetings and obligations that night time became the only part that felt wholly mine. I would arrive home mentally drained, yet yearning for some semblance of agency—some indication that I was more than my professional title. To sleep was to surrender to the next day’s relentless schedule. Staying awake, even when doing absolutely nothing of consequence, felt like control.

Now, the days of working my corporate job are long gone, but the habits survive. My current life, like every other day, brims with obligations, expectations, and the emotional balancing act between work and family. It is the nighttime slots of 11 p.m to 5 a.m that remains unclaimed on my calendar; where there are no meetings, deadlines, or anything to attend or care about. An illusion of having blank space to reclaim control emerges, even if that utopia arrives with a heavy price to pay.

My personal belief is that the quality of late-night solitude counterintuitively enhances the late-night time. While everyone else is considering themselves “off the clock”, keeps a low profile which enhances the feeling of stepping outside of normal days and deadlines while creating a flow like feeling making delusion of having suspended rules.

When I described this feeling to my therapist, I thought she would be alarmed by my sleep patterns. Instead, she nodded in a surprising way, as if she understood. “That’s what we call ‘me time deficit,'” she explained. “It’s common among caregivers and people with overly demanding jobs. When your brain feels chronically deprived of autonomy, it will prioritize personal freedom over biological necessities.”

This provided a lens through which I could understand why sheer willpower has never been enough to resolve this issue. The problematic behavior is not a matter of discipline, rather a lack of balance in my actual life that I’m trying to fix in the most misguided manner possible during biologically restorative hours.

The procrastination associated with “revenge bedtime” becomes more self-destructive in the digital context. Devices are designed to offer endless streams of content that require no effort to access and are perpetually curated to maximize user engagement. Unlike reading a book, which could indeed help me fall asleep, through digital means there are no natural stopping points. There’s always another video, another article, another post to scroll to. Even my engagement shape the content – the longer I stay, the more personalized – and thus more compelling – it becomes.

While working in technology, I contributed toward crafting some of these engagement strategies. In particular, we focused on how to mitigate “session endings,” which is our euphemistic clinical term for when a user decides they have had enough and closes the app. We designed algorithms to anticipate and counter disengagement by serving users particularly compelling content at critical moments. We built endless scroll and autoplay functions specifically to eliminate natural breaks that enable users to disengage or reevaluate their decisions.

I now find myself trapped in the very snare I helped design. The technology that keeps me awake isn’t evil, but it is working exactly as intended – engaging users to a fault. The applications don’t know, and frankly could not care less, that my bedtime was hours ago. There is no way for them to understand or bypass the fact that the user on the other side of the screen is operating far outside healthy parameters.

The impact of this behavior is tiring, but the consequences extend far beyond feeling exhausted. There are parallels with chronic sleep deprivations working life and personal life as it brings forth more complications for an individual to handle. I become less patient. I tend to run out of creative ideas for work. I am gradually sleepless. The impact is problematic as it means the individual ends losing control of the circadian rhythm, making it harder to get sleep in the future.

Over time, I have tried and tested several solutions. I have even gone to the extent of setting alarms for myself that would signal it was time to go to bed. Banning myself from using screens until a certain timetable and locking myself out of the phone until bedtime has passed. Not having my devices was only keeping me away for a small duration, as I cleverly always bypassed my passive safeguards.

Arguably my most brilliant way that I found to outsmart my strategies was going around setting elaborate screen time gates for myself. I had to only find out that taking less than a second to reply “just one more minute” together with clicking “yes” numerous times to get past all the final prompts allowed me out of the prisoner that I designed for myself. My focus shifted towards figuring out how to game my own rules of using the phone, effectively transforming the bedtime battle into a beatable mobile game, but paradoxically, I spent up to hours fighting my own coping mechanisms that I built for myself instead.

The most helpful interventions, I’ve come across, pertain to the environment rather than technology. For example, creating a bedroom as pleasant as possible, with a good mattress, optimal temperature, and comforting sounds, tips the balance toward sleep. Custom screen-free winding down sessions signals to my mind the day has indeed finished, disengaging with work and transitioning into relaxation mode. Physically flipping pages of books is appealing because it lends the stimulation my mind craves without forced content scrolling.

However, the most impactful one is still trying to solve the feeling of pseudo time scarcity for me during waking hours. I’ve tried to implement blocks of actual personal agency during the day, which I wildly labeled freedom. In actuality, these are not simply breaks between productive sessions, but contoured gaps for whatever I feel like doing. More often than not, these gaps become the perfect time for reading or viewing pre-recorded content.

The very first step to claiming this time seemed almost reckless, like I was robbing my productive work hours. But I now realize that these intentional breaks do, in fact, work wonders with my functioning on the whole. When personal liberty is not confined only to the depleted last hours of the day, both my work and my sleep improve. The revenge aspect of bedtime procrastination dissipates if there is less to take revenge to.

Let me be honest; I’m not claiming I’ve resolved this completely. At the moment, it’s 1:42 AM. I’m still tapping away at my device. Old habits die hard. But trying to make sense of the underlying psychology has let me approach this behavior with empathy instead of harsh self-critique. I’m not just making poor choices—there’s a legitimate self-autonomy and personal time need being pursued, even if it’s in a futile manner.

Should you find yourself trapped in a late night screen time and sleep deprivation cycle, know this – the answer doesn’t lie in a strict bedtime but instead more unstructured time during the day. Your brain is highlighting a critical concern regarding your need for control and personal decision-making. Understanding how to meet that need without sacrificing the restorative biological mechanisms along with other experiences fundamentally relies on.

As for myself, my current plan is to finish this paragraph, shut my laptop, and try to get five hours of sleep prior to my meeting. And maybe I, too, will set aside twenty minutes in the middle of the day tomorrow to indulge in reading for pleasure – a small act of reclamation that might transform my evening surrender to sleep into a moment of restful self-care instead of defeat.