I was attending my daughter’s ballet recital and the breaking point had reached. While being her ‘first fan’ sitting in the third row, my brain went on autopilot to work emails and twitter, even the score of a random basketball game I didn’t bother caring about. It gets worse. My daughter had a solo to perform, something she had practiced for rigorously and come the moment, I had my phone on record and was checking the notifications on my personal screen and digital window.

What I captured was a visually pleasing piece but lifeless video – locked off, perfectly framed and unzombified. From her dance performance to my daughter’s moment, I had indeed missed a lot by focusing on dabbling out multitasking online.

All of this clicked for me as I closed my phone for the day, full of resentment. The feeling you get yourself bound to something so fragile as a glass box and then realize the other end of that relationship no longer offers mental engagement. Where your most socially lifeless appliance changes from a shackled partner to an endless shoal, is a tough reality.

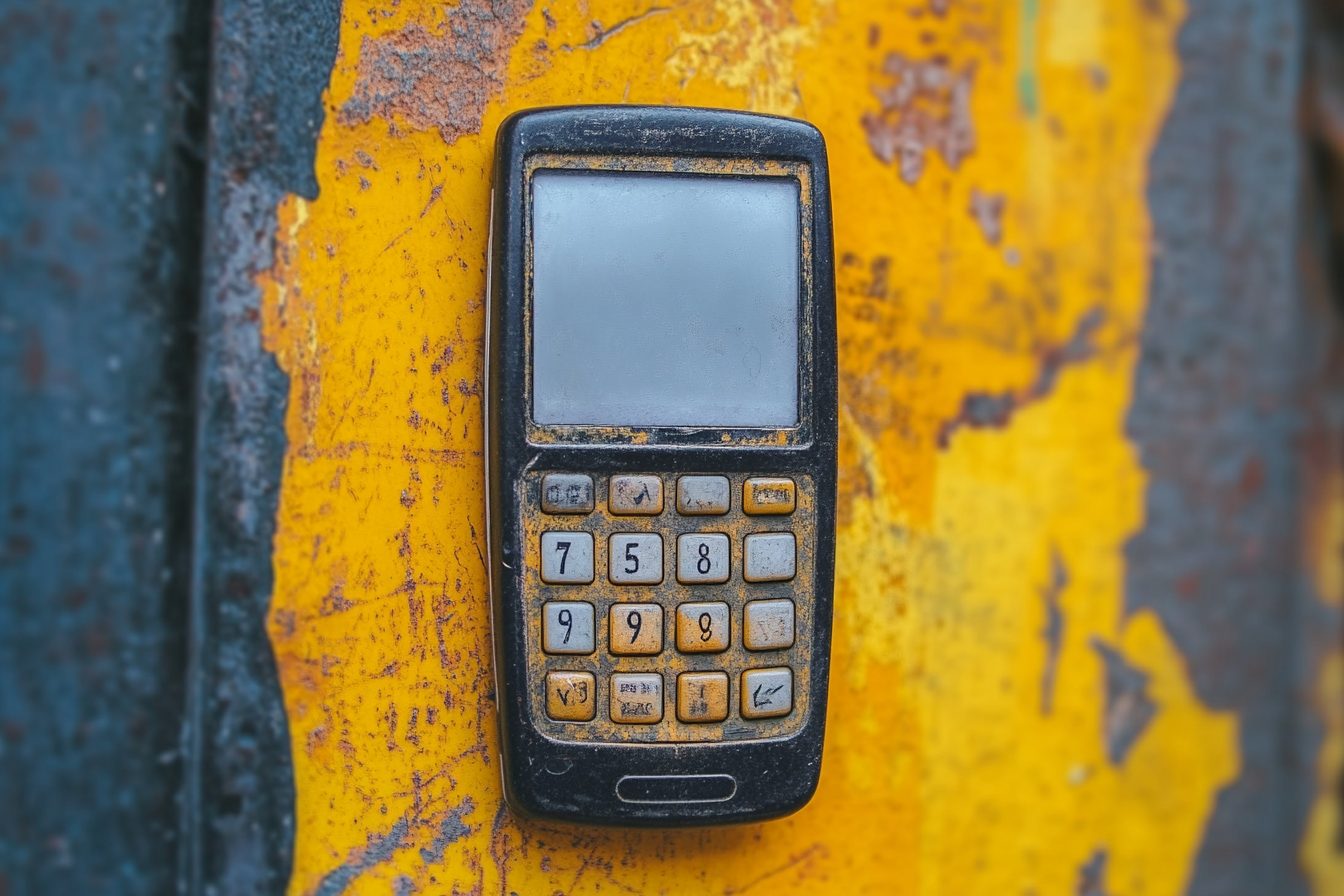

So I went ahead and did something pretty extreme. Immediately, I picked up my car and headed to a mobile shop to get myself the most basic flip phone they offered. This was the $40 type that could only make calls, send text messages (laboriously, through multi-tap), and perform absolutely nothing else. No applications were offered. There was no camera or internet connection. It was a phone that was in existence only to be a phone. After purchasing the phone, I transferred my SIM card and proceeded to power down my smartphone. I then decided to lock it in my desk drawer for one full week.

That, well, I think, marked the closest to social suicide I have ever done in my adult life. Depending on how one views the situation, that could have been profound digital detox.

Still, from a purely physical perspective, the first day was the most uncomfortable. This period forced me to undergo what I can only feel phantom phone syndrome. That is the state of constantly thinking one is missing something. Quite a lot of times, I tried reflexively reaching for my pocket. Considering clue moments of boredom or uncertainty, my hand instinctively reached for a device that was absent. Waiting in lines for coffee, riding lifts, and being stuck at red traffic lights were activities that in no way shaped my life, but after being freed from the monotony of time, I was met with the opportunity to escape a suffocating structured schedule.

By the afternoon, the mild anxiety began creeping closer to full-blown panic. I had completely lost touch with the world around me and felt like I was in a different dimension since I was no longer able to receive the constant information feed from my smartphone. What event was currently taking place? What was the general population discussing in regard to today’s happenings? Were there any attempts made to contact me on platforms that I could no longer access? The physical manifestation of intense FOMO in the form of restlessness mixed with the inability to concentrate on one singular task was very real.

The social awkwardness started swiftly. I contacted a friend with the intention of having lunch with him, which took me four times longer than usual due to my flip phone’s numeric keypad. He instructed me to check us in on the waiting list app, to which my answer was no. While waiting for the food, he asked me to split the bill using a payment app. Once again my answer was no. By the end of lunch, we were both irritated with one another despite being forced to interact socially due purely to my technological limitations.

The work hurdles were even greater. I had shared my plan with my team members, but the fact that I could not be digitally reached turned out to be far more troublesome. I did not attend a meeting because access to its calendar had been sent through an email which I could not check while on the move. A shared document was asking for my contribution, but until I got back to my office, it was impossible for me to access it. This experiment, which was supposed to be personal in nature, was impacting all my colleagues and demonstrating the extent to which our work ecosystems are intertwined and dominated by smartphones.

Day three showed the first signs of some unforeseen advantages. I had no notifications to distract me, which meant that I was able to focus during meetings and not multitask in a manner that has become commonplace. While attending meetings, I had to stop staring at my phone as I started taking notes on paper which, according to some studies, helps in memory retention. When waiting for an appointment, I actively pin my attention to the real-life environment instead of screens. I interacted with strangers. I began noticing the subtleties of the architecture on hundreds of buildings I had passed a myriad of times.

The most radical adjustment occurred in my family life. With no means to check email “just one last time” before bedtime, I had more time in the evenings. I was reading actual books – the type that can be held in hand – and completing more pages in three nights than I would have in a week during reading months with digital interferences. I no longer had to restrain my conversations with my wife to functional exchanges about schedules, which evolved in her and my meandering discussions we used to have before screens invaded our lives. I played board games with my daughter and, for the first time in quite some time, gave her my undivided attention.

Consequently, sleep immediately improved. I no longer had late night scrolling; therefore, exposing myself to blue lights, so without mental stimulation, I was finding myself feeling drowsy around 10:30 PM, while previously, I wouldn’t go to bed until midnight or later. Now, I was using a traditional alarm clock that isn’t a phone, so I no longer started and ended everyday staring at screens – so seamlessly. Because of these changes, each day became devoid of screens, meaning my mornings calmed, in turn becoming devoid of digitally shackled demands confined in my pockets.

With the advancement of the week, my social interactions had missed the mark. I neglected to see any birth announcements made available for viewing via Instagram. I missed the spontaneous post-work-hour gatherings that were organized in a chat room on a site inaccessible for me. One of my clients became increasingly tryed waiting for my email response. My friends started asking queries in the form of, “You must be busy answering this right now, but…” My digital absence was perceived, not as a conscious decision, rather a mindless, thoughtless choice and, or, impolite absence.

After 5 days, I had adopted some odd new habits. During the day, I would make use of my flip phone. The lack of notifications improved my focus but, I would spend the evenings going through a back log of messages for an hour. I was defeating the goal of this experiment, yet I was forced to confront a troubling reality – in today’s world, the option to be completely off digital services does not exist. The primary issue is not discontinuing the use of smartphones, but creating a more balanced and healthier paradigm with the devices.

How rapidly and thoroughly smartphones have transformed basic social expectations in just a short period of time was the most striking part of the experiment. A friction-less social life requires the minimum of what was considered impossible only fifteen years ago: responding to messages immediately, accessing any information on demand, documenting every experience with photos and pre-planned navigating to unfamiliar locations. Choosing to completely disable such functionalities, even for a short period, changes personal experience defining relationship with socio-technical systems offsetting these expectations, which are deeply integrated into modern life.

Along with socio-technological smartphones systems, everyday routines have also been outsourced relied to smartphones, as demonstrated in the flip phone experiment. I was unable to use the QR code menu at a café or the takeout app for the restaurant. Without the city’s parking app, I could not pay for parking, and boarding my flight required printing the boarding pass beforehand as I couldn’t access it on my smartphone. What should have been mundane tasks demanded additional planning, creating a cognitive burden typically absent for smartphone users without sophisticated planning routines.

Most of the conversations I held were particularly eye-opening. During a dinner party on the sixth day, I brought up my ongoing experiment. I was only expecting to incite some mild curiosity and maybe even laughter, which did not happen. Instead, my experiment triggered a discussion that lasted an hour in which every single participant shared their complex feelings regarding smartphone addiction. One participant confessed how she keeps her phone in a water-proof case even while taking a shower. She argued how not being able to talk to people for ten minutes was so miserable that the phone was a necessity to keep within reach. Another shared how he constantly feels phantom vibrations from his phone that has no ability to be in his pocket. A third shared how she has anxiety dreams stemming from the worry of losing internet access.

None of them took pride in these habits, but none offered a viable solution to change them either. Society as a whole now seems to be suffering from smartphone addiction. The smartphone changing from a useful device to an absolute necessity showcases how opting out—even in small amounts—seems to direly costly for consumers on a social level.

Right after the week ended, I walked towards the drawer that stored my smartphone. Even now, I experience mixed emotions regarding the situation. Part of me feels the need to surrender to the fragmented attention span and distractions I so desperately wished to escape from, while another side experiences the longing for connection that is only provided by my smartphone. The experiment’s goals would be much easier to attain if I did not modify my boundaries, and so I decided to get rid of most of the boundaries I put in my original expectations.

While my most valuable week of the year was coming up, the new perspective it offered was even more exciting. Without my smartphone’s ever-present distractions, I realized exactly when and why I reach for it. Some interactions are undeniably beneficial – seeking directions, documenting worthwhile memories, or acquiring information to make conversations more interesting. Yet, others clearly diminish my quality of life – mindless idling, responding to work messages during family time, and multi-tasking during meaningful moments.

This new understanding has helped me do many things differently. Now, I don’t take my smartphone to my meals, during my meetings, to my daughter’s engagements, and I don’t actively participate in her activities. I’ve removed social media apps from my phone and reinstalled them only during designated timeframes when I actively choose to engage. I’ve disabled all notifications apart from calls and texts from family. Otherwise, my phone will now charge overnight in the kitchen, rather than beside my bed.

These alterations aren’t indicative of rejection of technology, but rather, purposeful intention of my relationship with it. The primary lesson from my flip phone experiment was that the actual problem isn’t smartphones themselves, it’s the habitual, mindless usage and unrealistic societal standards that accompany them.

Would I recommend a flip phone detox to others? Yes, with written disclaimers. Total digital disengagement is likely impractical and undesirable for most individuals, but a temporary retreat can offer invaluable insight toward habits which have become invisible due to overuse. Even a single weekend with limited access can unmask digital tools that genuinely assist and those that have turned into unexamined crutches.

Neither total digital immersion, nor complete disconnection offered the single greatest benefit. Rather, the most transformative experience arose from deliberately selecting when to engage with technology and when to pause: a mindful approach. The smartphone ranks as one of, if not the, most powerful devices created by humanity for individualistic use. The critical question to address is how to guarantee that it stays a tool, not an external force that uncontrollably dictates our behavior devoid of conscious decisions.

For my part, I have retained the flip phone. When I choose to be particularly mindful, it serves as an alternative option, and it’s kept in my glove compartment as a reminder. During my experiment, I had a worrying realization that the flip phone serves as a backup. Without my smartphone, I felt not just unplugged, but close to inept at functioning in the world I inhabit. That sort of dependency needs to be checked regularly, and even if complete escape isn’t the solution, a blend does help.

Next month, my daughter’s next recital is coming up. This time, I will ask someone else to capture it on tape. I intend to fully immerse myself to her performance, not through a screen but in reality. Though the moment will not be digitally stored on my personal device, it will be preserved in a lot more places where it really counts – in my lived experience and memory. That is something no application can replace.